- hot-spots

- nuclear issues

- USA

- Three Mile Island accident

Problems

Three Mile Island accident

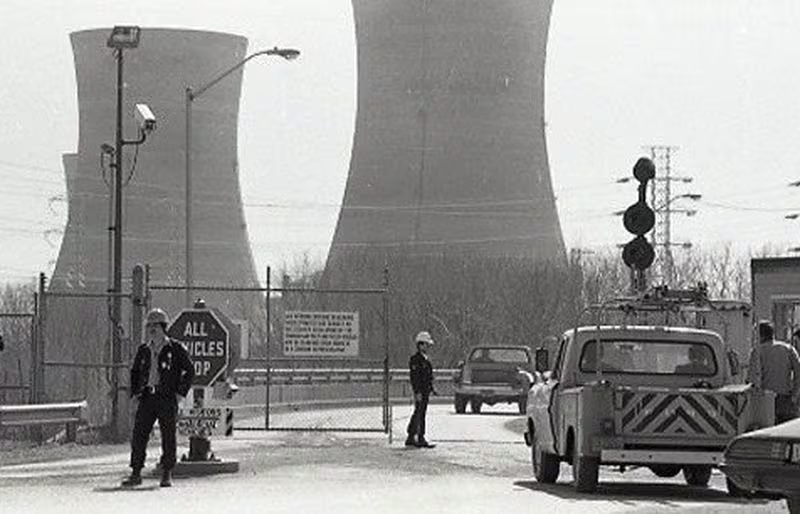

The Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor, near Middletown, Pa., partially melted down on March 28, 1979. This was the most serious accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history, although its small radioactive releases had no detectable health effects on plant workers or the public. Its aftermath brought about sweeping changes involving emergency response planning, reactor operator training, human factors engineering, radiation protection, and many other areas of nuclear power plant operations. It also caused the NRC to tighten and heighten its regulatory oversight. All of these changes significantly enhanced U.S. reactor safety. A combination of equipment malfunctions, design-related problems and worker errors led to TMI-2's partial meltdown and very small off-site releases of radioactivity.

Health Effects

The NRC conducted detailed studies of the accident's radiological consequences, as did the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now Health and Human Services), the Department of Energy, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Several independent groups also conducted studies. The approximately 2 million people around TMI-2 during the accident are estimated to have received an average radiation dose of only about 1 millirem above the usual background dose. To put this into context, exposure from a chest X-ray is about 6 millirem and the area's natural radioactive background dose is about 100-125 millirem per year for the area. The accident's maximum dose to a person at the site boundary would have been less than 100 millirem above background. In the months following the accident, although questions were raised about possible adverse effects from radiation on human, animal, and plant life in the TMI area, none could be directly correlated to the accident. Thousands of environmental samples of air, water, milk, vegetation, soil, and foodstuffs were collected by various government agencies monitoring the area. Very low levels of radionuclides could be attributed to releases from the accident. However, comprehensive investigations and assessments by several well respected organizations, such as Columbia University and the University of Pittsburgh, have concluded that in spite of serious damage to the reactor, the actual release had negligible effects on the physical health of individuals or the environment.

Impact of the Accident

A combination of personnel error, design deficiencies, and component failures caused the TMI accident, which permanently changed both the nuclear industry and the NRC. Public fear and distrust increased, NRC's regulations and oversight became broader and more robust, and management of the plants was scrutinized more carefully. Careful analysis of the accident's events identified problems and led to permanent and sweeping changes in how NRC regulates its licensees – which, in turn, has reduced the risk to public health and safety. Here are some of the major changes that have occurred since the accident: Upgrading and strengthening of plant design and equipment requirements. This includes fire protection, piping systems, auxiliary feedwater systems, containment building isolation, reliability of individual components (pressure relief valves and electrical circuit breakers), and the ability of plants to shut down automatically; Identifying the critical role of human performance in plant safety led to revamping operator training and staffing requirements, followed by improved instrumentation and controls for operating the plant, and establishment of fitness-for-duty programs for plant workers to guard against alcohol or drug abuse; Enhancing emergency preparedness, including requirements for plants to immediately notify NRC of significant events and an NRC Operations Center staffed 24 hours a day. Drills and response plans are now tested by licensees several times a year, and state and local agencies participate in drills with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the NRC; Integrating NRC observations, findings, and conclusions about licensee performance and management effectiveness into a periodic, public report; Having senior NRC managers regularly analyze plant performance for those plants needing significant additional regulatory attention; Expanding NRC's resident inspector program–first authorized in 1977–to have at least two inspectors live nearby and work exclusively at each plant in the U.S. to provide daily surveillance of licensee adherence to NRC regulations; Expanding performance‑oriented as well as safety‑oriented inspections, and the use of risk assessment to identify vulnerabilities of any plant to severe accidents; Strengthening and reorganizing enforcement staff in a separate office within the NRC; Establishing the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, the industry's own "policing" group, and formation of what is now the Nuclear Energy Institute to provide a unified industry approach to generic nuclear regulatory issues, and interaction with NRC and other government agencies; Installing additional equipment by licensees to mitigate accident conditions, and monitor radiation levels and plant status; Enacting programs by licensees for early identification of important safety‑related problems, and for collecting and assessing relevant data so operating experience can be shared and quickly acted upon; and Expanding NRC's international activities to share enhanced knowledge of nuclear safety with other countries in a number of important technical areas.

Gallery

4Timelines

2019

January 01

In the aftermath of the accident, cleanup and decontamination efforts continue for several years, and Unit 2 is permanently shut down. Unit 1, which was not affected by the accident, continues to operate until its planned retirement in 2019. The accident prompts a reevaluation of nuclear safety regulations and a greater emphasis on training and safety culture among nuclear plant operators. The incident is classified as a level 5 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, making it one of the most serious nuclear accidents in history, but the health and environmental impacts are ultimately less severe than initially feared.

1979

April 09

By April 9, the reactor is successfully cooled and stabilized, and the release of radioactive gases is greatly reduced.

April 01

Operators realised there was no oxygen in the pressure vessel, so the likelihood of the hydrogen bubble exploding was very slim: the bubble was vented and reduced, and the threat of meltdown or a serious radiation leak was brought under control. President Jimmy Carter visits the plant and reassures the public that the situation is under control.

March 30

11:45 am A press conference was held in Middletown, in which officials suggested that a bubble of potentially volatile hydrogen gas had been detected in the pressure vessel of the plant. 12:30 pm Governor Thornburgh advised that pre-school children and pregnant women evacuate the area, closing various local schools. This, amongst other warnings and rumours, triggered widescale panic. In the following days, some 100,000 people evacuated the region. 1 pm Schools started to close and evacuate students from within a 5-mile radius of the plant.

March 29

As the cooldown operation continued, more radioactive gas was vented from the plant. A nearby plane, monitoring the incident, detected contaminants in the atmosphere.

March 28

At 4:00 a.m., a water pump in the secondary cooling system of the Unit 2 reactor at Three Mile Island fails, triggering a series of events that result in a partial nuclear meltdown. Over the next several hours, a combination of design flaws, operator errors, and equipment malfunctions lead to a loss of coolant and the release of radioactive gases into the containment building. Around 7:00 a.m., the plant's safety systems automatically shut down the reactor, but pressure inside the reactor continues to rise. At 7:30 a.m., plant operators attempt to manually vent steam from the containment building, but a valve gets stuck open, allowing coolant to escape. Over the next several days, plant operators work to stabilize the reactor and contain the release of radioactive gases.